(First published in Metropolis M, No 1 February/March 2005)

Stuart Bailey:

Over the past year you've organised a series of salon meetings alongside your regular practice. Can you briefly describe their location and nature?

Mark Aerial Waller:

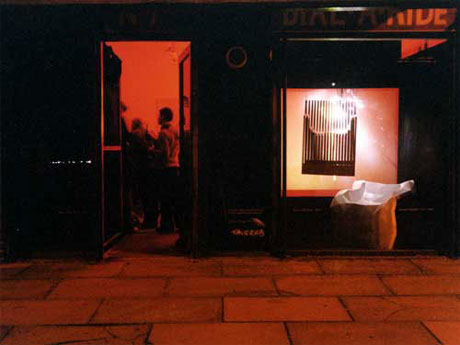

Taverna Especial is situated on a Dawn of the Dead-like deserted shopping parade along Hackney Road in east London, in a ground floor space which used to be the local Dial-A-Ride cab office. It grew out of - and now runs parallel to - a film salon called The Wayward Canon, which started out in the same cab office showing films which were made commercially but had fallen into the margins of cultural importance. These included the pan-generic films of Edgar G. Ulmer, Art Schlock of Dario Argento, Dennis Hopper's directorial films, and George Franju's post-Surrealist pre-nouvelle vague masterpieces; films which slid on cultural ice and fired in all directions of critical reception. It began with small scale meetings of a quite critical nature. Each one was accompanied by a lengthy introduction, and people actually made notes during screenings. The Wayward Canon continues to run, but no longer in the cab office, as it now engages with durational all-night events for larger audiences.

Giles Round and I chanced upon Taverna Especial in the summer with intention to use the cab office to look at singular works. It's named after a bar on Portobello Road in west London where Lucian Freud takes his young models and assisants for pre-studio coffee. The place is full of witicism and sour-faced Spanish waiters, as well as the young no-good bohemian wasters who have now made their exodus to the roads surrounding the cab office and local flower market. So the name is also about real estate in a cryptic way. Anyway, the format of the Taverna Especial salons involved the artist arriving around 6pm with the work, which would be quickly installed while the other guests arrived. The grand gesture and potentialised concentration of showing one piece for exhibition has been the main theme of the evenings, followed by white wine and pizza as a kind of retreat from the viewing situation. Giles and I wanted a direct meeting with the contemporary work, like queuing at the Louvre for the Mona Lisa or for The Last Supper in Milan, rather than the cursory glance that contemporary art usually solicits. Maybe it's also to do with making art into cinema, the single screen concentration and food and drinks afterwards.

Stuart Bailey:

I've recently had the recurring experience of attending large scale exhibitions - both museums and group shows - and similarly focusing on a single piece of work. Not consciously at first, more by default. It used to make me anxious, feeling obliged to take in everything, but since noticing myself do it, this narrow focus seems increasingly natural. In a favourite article of mine, Julie Burchill describes casting off the layers of heavyweight Sunday newspaper sections until she's left only with those items she already has an intense interest in. I think Hockney described a cross between these two attitudes: a wave of drowsiness upon entering a gallery, and an impulse to buy the catalogue and return home immediately to the safety of an armchair. I'm interested in how you seem to define the salon by what it isn't as much as what it is. Did the contributors choose their single works very consciously in light of this concentrated context? And did the evenings themselves feel cinematic, as if you were all part of a film - artists in a film about an art salon, or zombies in Dawn of the Dead? I vaguely remember you relating that some evenings had a kind of hallucinogenic quality. Perhaps that had something to do with the summer.

Mark Aerial Waller:

Taverna Especial has been a constantly evolving system, starting with a curation by Jo Stella Sawicka of a Giles Round piece nailed to the wall with people looking on. The evening grew as people we knew dropped by to say hello, not knowing anything about the event as we didn't realise that there was an event happening anyway. They stayed, going off at some point to find food and drink to bring back. Then we realised what was happening. There was heated conversation about the work. Some people were riled by the work's nonchalance, so stayed to continue the conversation. I suppose that the fast realisation of something occurring was hallucinogenic, especially with the arrival of new guests who acted as players in the emergence of event. Another event operated as a lure. We offered to invite people back from the tail-end of a gallery preview. The guests were mainly unaware of our intention to show a video, recently lent to me by an artist called Ben Callaway, called The Struggle. It involved text-messaging detonators and Greek heroic imagery also shot in a fluorescent-lit Lambeth council office, insurgence boiling over like a Céline novel. The audience this time were completely non-plussed with the art content, thinking that the evening would be just about alcohol.

Stuart Bailey:

Is alchohol - or any other drug - necessary here? Could you conceive of Taverna Especial without alchohol? I went to an alchohol-free opening not so long ago and people were genuinely outraged.

Mark Aerial Waller:

Maybe you'd like to come round and set up a drugs morning sometime in late spring when the sunlight is sharp and low. The My Kleine Fassbinderbar event became the most fluid in eroding the horizon between watching a film and the film becoming a 'ritualising machine'. The scenes in the series were becoming hot, steamy sex scenes in the cold desolate Alexanderplatz. Two people I knew had disappeared from the coffee tables and sofas. I was selling sausages from the kiosk watching the show. Another friend was snooping around, looking for the toilet I think. She made a mistake and opened the door slightly on these lost two who were engaged in some kind of perverse role-playing act, one seated half-undressed and the other kneeling with trousers unbridled. They didn't notice her, but she came back to announce the news to me and two others, who went together to have a look and felt deeply embarrassed at their curiosity, faced with the two in flagrante, who were now looking back at them ...

We then thought it may be interesting to move into the idea of a rental space show. A designer friend of mine wanted to do something there, and was keen to pay for it, so we went along with the idea. We stipulated that only the windows could be used, and it was amazing. His designer associates came and mixed with the regular Wayward Canon and Taverna Especial people. The artists were looking at his design work without being told that's what it was. There was a very relaxed atmosphere with people lounging on the bed and black vinyl sofa, meeting in this gap between house and art opening, with design being shown covertly.

The Wayward Canon events were to do more with the re-representation of films, and each evening had a slightly different approach. I think it was to do with re-evaluation of critical approaches, so for instance O Lucky Man! was presented as a study of psychic phenomena and schizophrenia. Actors played multiple roles, the main actor followed the trope of the visionary film protagonist. Dead of Night was a study in boundary theory. Judex was an exposé on the French underground Masonic system. Billy Jack was to be seen as a pro-American movie, my propaganda for friendship with the US freedom movement. Edgar G. Ulmer was an ongoing monument to one of the most resourceful directors ever; he exceeds Lang, morphing from German expressionism to Hollywood Horror to Yiddish Romanticism and Black Jazz to B-movie Noir and Sci-fi.

Stuart Bailey:

How exactly did you re-represent the films? - through the title of the evening or an introduction, or was it more allusive? Is part of the whole idea that the audience is not quite sure of what's going on? Are you trying to throw people? It sounds like you're as interested in the mechanics of the evening as much as showing the individual works and films.

Mark Aerial Waller:

The Wayward Canon had email invitations in bright colours and a short text introducing the film as well as a wayward critical entry into looking at the film, so people had a sense of what they were going to watch. It was more to assist people in looking tangentially at films which seemed to have a covert reading. In fact the medium of film is one were most energy has gone into the development of covert language, perhaps ever since the introduction of the Hays code for decency in film. Maybe it actually shouldn't be seen as cryptic, rather the development of a multi-layered language. This is where the humour, horror and tension of cinema resides, within the shadowy half-pronounced areas.

Stuart Bailey:

Do these salons have a limited life span, or only work with a limited number of people? If so, how do you tell when the time's up or the numbers are too big? Then what happens?

Mark Aerial Waller:

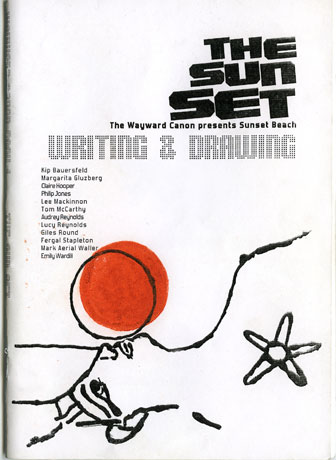

Yes, the Wayward Canon as a micro salon could only sustain itself for a limited period of time; there was a need to change the participants. This is why I opened it up to a broader structure involving an event and accompanying publication. The first event was called 'The Sun Set', referring to the title of the TV series Sunset Beach. It alludes to a small social group, such as The Bloomsbury Set, as well as a sun-worshiping cult, or indeed a film set. What happened here is that around ten people - the eventual contributors to the publication - came to the cab office to watch episodes of the TV series, which operated as a kind of salon in itself. Each participant watched an hour-long episode of the series and made fictional, theoretical and poetic responses to it, or used it as a catalyst for the production of new work. The responses were mainly engaged with the fractured sense of time throughout the series; an eternal present woven through with past and future. The same people then came to the wider public event, where the publication was sold as a series of opera notes. The contributors didn't seem to be on the spot like artists at a group show, as the publication seemed marginal to the video and social event, although in terms of content it was the main event.

Stuart Bailey:

Why opera notes? It reminds me of a related idea a few years ago when Sonic Youth played a show at a high-class New York concert hall, complete with the evening's programme laid out on velvet seats. The sort of idea that has to be over the top and dumb to work. You seem to combine high and low without it seeming concieted: opera notes in a taxi rank; taking notes on the couch and fucking in the back room; white wine and pizza ...

Mark Aerial Waller:

Yes, in a way: I meant opera notes as in soap opera notes. But I think Taverna Especial's success is more to do with the retreat from the formal event, towards concentration on the work, or perhaps a shift in balance, where the unexpected cursory element could become the focus. For example, the cusp of design and art, or the way the audience might not realise it's the audience. A kind of inverse of covert surveillance filming. It's more to do with that than wrong-footing people. I like your use of the term allusive. I think that is the key to much of this project. But to enter into the eye of the allusive, taking care not to wander off and be thrown sideways by the vortex of prejudgement.

Stuart Bailey:

Recently I wrote about this sense in relation to another optical metaphor, sunspots, and how when you try and look directly at a sunspot burnt on your retina it skips off to the side, because you never look at the sun with the exact centre of your eye. Over its course of events so far the salon seems to describe this also - how the most interesting things are happening in the gaps between what appear to be the official ingredients, or what appeared to be such at the beginning. The situation is fluid. Your description also recalls Lars von Trier's recent The Five Obstructions in which his old mentor is commandeered to remake his own 1950's classic short film five times over, with different limitations. Everyone I've talked to complains that all five resultant films are terrible, but to me that's the whole point. The structure and the failure is everything, although to describe it as such is also misleading, because the formalism and depression is countered by a disobedient momentum - a mocking self - consciousness and intangible glee that carries it along. 'The Sun Set' seems to have a similar life of its own; gears are set in motion, and though the outcome is unknown, you trust it's going to be an interesting process. So the salon's raw material - the writers - come for a preliminary private meeting, a kind of briefing, then drift off into the night (or dawn) to prepare for the public salon proper, where both groups observe the other from different viewpoints. Is that about right? I imagine from your own viewpoint as curator/riddler/hot dog salesman, both stages are equally important and interesting - and are both equally pieces of work in themselves.

Mark Aerial Waller:

Yes, the meetings and personal screenings were just as important as the final event. The project created a sense of community, a community which also had willing critics, who questioned the motivation of the project as a starting point. What I am trying to say is that the project doesn't come purely from the position of the fan. Some contributors found the programme irritating or banal, but nevertheless engaged with the series on those grounds. I'm thinking of Fergal Stapleton's contribution, which was in the form of a religious proposal for a suburban cult, outlining phases of transcendence for the spritually-depleted members.

Stuart Bailey:

Is there any deliberate reference to salons of the past; or of art being shown, if not necessarily exhibited, in the homes or studios of their owners? Warhol or Brancusi, for example? Or did Taverna Especial just evolve from circumstance, as you seem to suggest in describing the Giles Round evening?

Mark Aerial Waller:

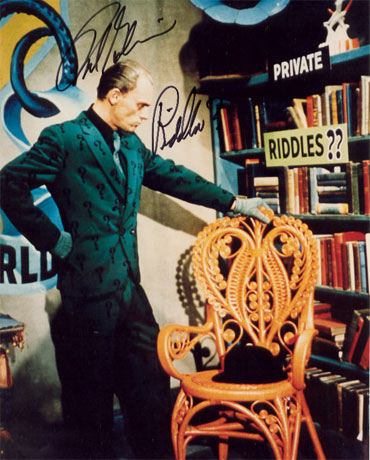

My first point of reference is The Riddler from Batman and the Gotham City Museum. His invitations were always a joy: paintings and green smoke on inclined floors, followed by a fight. That is my ultimate salon. The second point of reference is Georges Franju, who saw and made films as 're-animating machines', rituals for bringing the dead back to life. He set up the Cin&eactue;mathèque Français with Henri Langlois, which was a kind of grave-robbing project to recover pre-Surrealist cinema serials such as Fantomas, Judex and Les Vampires. These were the films which influenced his Surrealist heroes as teenagers. His project wasn't nostalgic in the present sense of the term, it was a wish to really shift time zones, or give eternal life in a vampiric way.

Stuart Bailey:

I like the idea of a new work containing an old one, in a perverse act of preservation - active preservation maybe, or just simple re-activation. In Olivier Assayas' Irma Vep (more vampires) or, again, The Five Obstructions, the original works that fuel the new are lovingly embedded. Is this self-reflexive attitude part of your overall idea? I'm associating this with the scene at the end of one of the film's you showed, O Lucky Man!, when Malcolm McDowell walks into his own casting for the film with director Lindsay Anderson and the snake eats its own tail - or tale. Are you the Malcolm McDowell of Hackney, walking in on your own set?

Mark Aerial Waller:

Well, I hope I'm myself, but I see what you mean. Yes I think that the events are distanciated or objectified, but I'm not sure that I'm the central protagonist on the set, neither am I Lindsay Anderson. I think there is plurality in the way these micro salons work. People have to be accounted for, as there are not enough people for it to become a singular audience, who are separated from the event by their size and lack of individuality.

Stuart Bailey:

I suppose we become attuned to different aspects of films (or other art) at different locations, or if they're framed in different ways. The difference of someone seeing O Lucky Man or Sunset Beach at Taverna Especial, compared to the ICA, or at a Warner Brothers cinema, or on TV, or in a big town or a small town, or in different countries, or back in 1970, or on your own or with friends. Right now, displaced in New York, I'm very conscious of looking at European and American art through the other end of the telescope, and how it affects the reading. Is displacement part of the idea? Would you show Fassbinder in Berlin, or O Lucky Man in 1973, or is their slipping through the cracks exactly what makes them interesting now - is that the particular facet you're chasing after?

Mark Aerial Waller:

I have been interesed in showing Fassbinder in Berlin. Alexanderplatz still has the harsh edgey feel of the Döblin book, even though it is all new. But as you say, this would remove the obvious displacement and accompanying exoticism that the medium of film has to offer. I asked some Berliners recently about Fassbinder, who say it's hard to find him now even in the repertory cinemas. They say his work has dated, in terms of philosophy as well as style. However it did seem relevant here, showing Alexanderplatz to us London drunkards in a cold, socially discarded commercial unit in an unforgiving financial environment, trying - like Franz Biberkopf - to make good, keep warm and enjoy life a little bit.

Stuart Bailey:

Finally, is it significant that you've mentioned both Dawn of the Dead and vampires? In your other work as well as the salon and its contents there are recurring emblems of horror, legend and conspiracy.

Mark Aerial Waller:

Yes, like Franju, vampires and zombies are central to showing art, re-animation and being poisoned or infected with attractive ideas, with lots of sequels and re-emergences. I think that Taverna Especial is about the understanding of circumstance, allowing for chance to enter and being conscious of the moment. A-navigating in the drift.