The exhibition of Brion Gysin's Calligraffiti of Fire at the October Gallery in London is a major event. This is the first time the artist's legendary final work, executed in 1985, has been shown in Britain and the exhibition provides a unique opportunity to experience the painting in the context of the artist's small calligraphies and grid works whose fusion — the integration of order and chaos, the mechanical and the free-form — is absolutely crucial to the main painting. Curated by Kathelin Gray, a friend of Gysin"s, the show reveals the originality, power and beauty of Gysin's art, and also includes photographs of William Burroughs taken by Gysin on the launch day of Naked Lunch in Paris, and versions of the Dreamachine which the artist developed with Ian Sommerville — reminders of the key collaborations and radical explorations of different media which would inform Gysin's visual art.

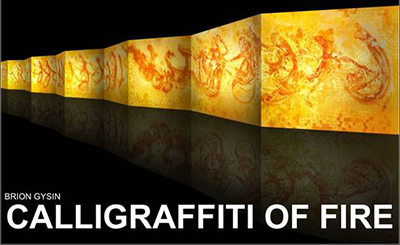

Brion Gysin, Calligraffiti of Fire, Exhibit Postcard

Calligraffiti is based upon the Japanese foldout makemono, and the hanging of the work at the October Gallery is a perfect solution to the painting's length and "concertina" format — the beginning and end panels (Gysin intended the picture be "read" from right to left in the manner of Arabic writing) have been angled to suggest the opening up and closing of the whole, while leaving the rest of the sequence flush with the wall. The structure of the makemono had a philosophical significance for the artist — "I Am the Artist when I Am Open. When I am closed I am Brion Gysin." — and this process of unfolding is effectively captured in the display. The painting was previously shown in Paris at the Sammy Kinge Gallery, and in Edmonton, and has also been exhibited in the context of Islamic art, but for fans and afficianados, and for those who truly care about painting, this is a very special celebration of Brion Gysin hosted by a unique gallery which has supported his work over many years.

Gysin had made a very few large works before Calligraffiti, including the great paper roll of gridded skyscrapers which he is seen painting in Antony Balch's film Cut-Ups — Burroughs left this painting in his apartment and it subsequently disappeared. There had also been the meter-long A Trip From Here To There, "my first Big Picture with stone-ground Japanese ink and British watercolours", painted in Morocco, as well as the "performance" painting which he made at the Domaine Poetique in the early sixties, a calligraphy executed with three wide Japanese brushes and an engraved roller on a large roll of photographer's background paper. Lawrence Lacina recalled the denouement of this event: "Brion . . . took a bow, then cut the painting off the frame, letting it curl up on the stage floor. He then picked it up, unrolled it and tore it into pieces (loud groans from the audience) and left the stage."

Calligraffiti Of Fire was based upon a small ten-panel fold-out makemono, upon which Gysin had drawn with Japanese oil pastels. Both the form and the theme of this work, Summer Fires 1965, were decisive, but in attempting to make a final large work — "I had always wanted to paint a big picture" — Gysin was seeking to transcend the earlier picture and to leave a definitive statement of his vision and his powers, a permanent, lasting work in paint on canvas which would make up for the exigencies and vagaries of fate, and his own auto-destructive proclivities. This time, the work would remain, as evidence and validation. It would be the artist's final work, a summa which would stand as testament to a visual art which had been an illustrious vocation rather than a glittering career. Gysin's lack of a studio and his financial problems had made the painting and storing of large works impossible and Calligraffiti of Fire is inevitably a form of redress — see what might have been, if life had been less arbitrary, and fate more kind. The painting would exemplify everything which prosaic, cruel circumstance had denied — big enough to fill a gallery, large enough to encapsulate a life.

Terry Wilson recalls the atmosphere of secrecy which surrounded the execution of the work in 1985 and Gysin's reluctance to discuss the painting apart from his admitted uncertainty about whether he had the strength and energy to realize his intentions. Gysin's great friend and supporter James McCann made the painting possible, generously providing the artist with materials and assistants and, for the first time in his life, a proper studio in Paris. This was the place and the space where a boundless vision and the physical limits of the body would meet. It would be absolutely the last possible work, and its very scale would challenge the suffering of the body, the fear of death, and the judgement of posterity. Gysin was known to a cognoscenti as an exquisite miniaturist, but his desire to create a big painting was inevitably a way of taking on the large-scale works of the Abstract Expressionists and calligraphic tachistes such as George Mathieu. Despite his disdain and defensive hauteur, Gysin wanted to be in that arena, if not of that company, although it is the length of Calligraffiti of Fire (1640 cm), rather than its height (130 cm) which is so striking — the work cannot be visually encompassed from a single viewpoint and must be traversed and "read" through space and time as an unfolding sequence, like walking down the corridor of a moving train. Gysin was aware of the contradictions inherent in the project — after all, imagining a future mankind in space, free of earthbound objets d"art, he had noted, "I can"t see anyone taking any huge museum-size canvases along." Well, he himself was going into space, and he would leave both his body and a museum-size canvas behind — the mortal and immortal remains of the late Brion Gysin.

Calligraffiti of Fire is much more than the form and theme of Summer Fires 1965 rendered on a large scale. When Burroughs looked at a Gysin painting and glimpsed, "a lot of people on fire . . . streaming with gasoline on fire across the whole picture . . . ", he was divining a paradoxical theme which runs throughout Gysin's life and work: fire as incendiary liberation, symbolic of creative powers, and fire as immolation and obliteration — now one, now the other, and finally the same: the spirit of life and its nemesis, gathered and burned out in the same flame. Crucially, Lacina describes the painting and destruction of the image at the Domaine Poetique as a homage to the Goddess Kali, observing: "There's no creation without destruction; there's no destruction without creation — Kali." In Tantra it is imperative to confront one's fear of death and the curse of chaos and discorporation — and by his creative and auto-destructive act, Gysin was attempting to placate the Great Devourer by taking upon himself the obliteration of his own work, eviscerating his own striving for transcendence and his pride in his own accomplishments. Although Lacina had rescued the dismembered picture and with Gysin's help restored it, it would nevertheless remain an essentially eviscerated work — the sutured body parts of a sacrificial rite, memento mori of an act of artistic suicide.

Brion Gysin, Calligraffiti of Fire, Painting, 1985

Kali was very definitely not the Divine Mother as far as Gysin was concerned, but a fearful and ferocious consumer of time. In his auto-destructive act, Gysin casts himself as Shiva who throws himself at Kali's feet in order to pacify her and halt destruction by simulating self-sacrifice — Kaligraffiti. Lord Shiva is often depicted as an archer destroying the Tripura fortresses of the Asuras. Gysin knew Eugen Herrigel's 1948 [Zen In the Art of Archery]5 and in his work he incarnated the zen philosophy of bypassing conscious control in the execution of the artistic act. But there is another specific and profound connection between Calligraffiti and archery. In the 1930s Gysin and Denham Fouts had fired burning arrows from a Tibetan bow from a hotel window down the Champs Elysées — a performance which terrified the extremely cautious Paul Bowles. This symbolic, mystical act — which was also a thoughtless piece of high jinx and youthful stoned anarchism — would resonate for Gysin in unsuspected ways: the trail of fire and smoke left in the air by the blazing arrow was in itself a perfectly self-destructive calligraphic gesture, as inspired as it was doomed, as memorable as it was transitory. "Art is the tail of a comet", Gysin would later claim, suggesting a creative act which burns itself out in space, and those flaming arrows of desire would become the trajectories of brushes and paint through space, leaving glowing traces of the actions which had fired them, concentration and effort unleashed at hazard. This analogy between calligraphy and fire, and between the flame of inspiration and the dangerous creative act, is present in the tradition of Taoist fire paintings, in which the character for a blaze, made with four strokes of the brush, may be exploded in the act of painting, creating an "Enbu" (dance of flames), embodying a fire running out of control, expressing the idea of fire through the destruction of the signifying radical or name, and projecting the feeling and experience beyond the conceptual understanding or referential signification . . . The word or emblem for "fire" is consumed by the very act of its own writing, which paradoxically conveys its meaning with extraordinary intensity, with power and heat. Likewise, Gysin's own personal ideogram, his calligraphic signature, is torn apart in Calligraffiti of Fire — the "radical" or character of his own "personal fire" is fired, time and again, across the ten canvases, distorted, sundered, obliterated, leaving trail flames blown down the boulevard of time.

Gysin's sign takes the form of a phallic bow, as if echoing the instrument with has impelled it — the arc of the brush through space before it shoots — fires — ejaculates its prima materia. Like Francis Bacon, Gysin even includes in the Calligraffiti a long thin flick and trail of white paint terminating in a strategically accidental drip, a petrified spermatozoa, the tail of a falling comet, and an onanistic offering to the fertility of vision. James Hillman has described Pan, the great Goat God, as the archetype of masturbation, an act which has creative significance "regressively far from consciousness", and Gysin's homage to Kali was also understood by Lawrence Lacina as significantly bound up with the music and rites of Pan in JouJouka: "The brush with yellow paint made sunny dancing glyphs; the orange brush splashed hairy swaths like Bou Jeloud in all his fury, brandishing his branch wand." It is this ancient Moroccan dance of Pan which Calligraffiti commemorates, a ritual which Gysin connected to the Roman Lupercalia, when boys in goatskins ran down the Palatine Hill, lit by flaming torches. Gysin was psychologically steeped in the myths and magic of Pan, and as well as a procession of torches, the Roman phantasmagoria, Calligraffiti may be read as conjuring Pan's true time of day, the blaze of noon, when the fields of grain shimmer and ripple in the heat and the air becomes a hot, flickering mirage, and yet time itself seems to stand still. This is the uncanny moment out-of-time which, as Hillman says, exemplifies nature at its most spontaneous and unaccountable, "headlong, heedless, brutal and direct, whether in terror or desire . . . all life at the moment of propagation or all death in the panic of the herd . . . Spontaneity remains an experience . . . outside ordering systems of explanation." Gysin and Burroughs both mourned the passing of Pan and "The Great God Pan is Dead!" was for them the exemplary elegiac of the extinction of nature and the eradication of the ecstatic feeling that everything in the world is alive, a single self-devouring, but self-recreating nervous system. In his last visual apotheosis Gysin links the spontaneity of calligraphy with the risk and riot of Pan on the run. Hillman: "The spontaneous panic out of noon's stillness reappears in the kobold, or little demon . . . said to cause panic and nightmare. This being too has a sexual connotation: it is phallic, dwarf-like, fertile, both lucky and fearful." In Calligraffiti it is Gysin's calligraphic personal sign which becomes the kobold, jumping and leaping through the picture space, the demonic essence of the psyche stretched and broken and transmogrified. These "creatures of the secret name" emerge in the bright light of day, monstrances derived from those secretive, miniature sprites who had danced through his drawings, his "jungle gyms", and the little creatures he once tried to point out to Terry Wilson as actually existing in the world, but who are so terribly hard to see. Gysin saw them, they were as "real" to "him" as "you" and "I". But like the little people of the desert encountered through hallucinogens, in Calligraffiti they are also fleeing the psyche, escaping the human domain, "fading out with demoniacal grimaces, shaking their fists. A great blast of sand sweeps down from the dune and envelops us all." In this sense, the exuberant Pan dance of Calligraffiti is also, necessarily, a funeral march. it commemorates as it celebrates a vanishing spiritual dimension. Gysin wrote, "Music, little Pan, not dead . . . It proven Pan not dead." But he also admitted, "There will be harrowing in my magic picture."

In his writing Gysin often evoked the heat and blaze of the desert and the Moroccan mountains in summer, the mythic Mediterranean and the islands of Greece, light flashing through the window of a bus, a field of burning grain seen from a darkened doorway, and transcendent visual hallucinations triggered in the nervous system by apocalyptic heat and light — "a swarming sting of the sun . . . burning bright to a fiery rose on the dunes running like molten orange gold. The day tortured eye." And: "the sun wrenched itself from the sky and fell sickeningly over the edge of the world . . . a rattle of fire across the Sahara." Hypnagogic heat visions, optical flares, summer landscapes on fire and running past the eyes like a burning film, a match head igniting, exploding white and blinding the eyes — these may all be glimpsed and felt in Calligraffiti of Fire with its hot, searing palette. An irregular grid of small yellow and orange squares is broken by a central void through which the calligraphy runs, a series of flames jumping from canvas to canvas, burning through the emptiness of space left by the fragmented grid patterns. The grid was used by Gysin to suggest the appearance of buildings and structures, the creation of a world of solidity and matter, while the illusory nature of this dimensionality is continually emphasised in his work — it is a game of Maya, of illusion, revealing mistaken perception and the deception of appearances, an endless process of undoing what has been created. In Calligraffiti parts of the calligraphic strokes show roller patterns of superimposed yellow grid lines, emphasizing the surface and facture of the painting, declaring its illusory construction, as if the desire to create and build appearances will continue after the destruction by fire. . . Or perhaps this is terminal, and these are the glowing ghosts, the last vestiges of Gysin's "jungle gyms" caught in the furnace at the final moment before they are extinguished. Calligraffiti is indebted to the 1950s and early 1960s Gold Paintings and Fire Paintings of Yves Klein, an artist Gysin admired greatly at a time when many in the art world considered Klein a charlatan and a buffoon. The two artists had a shared fascination with different esoteric traditions, from zen to alchemy and Taoism, and they both combined regular grid structures with the directed yet random act of the gestural mark. Calligraffiti suggests a summation of Gysin's own merging of the grid and the calligraphic, and a hybrid homage to Klein's brilliant grids of gold leaf and to his calligraphic strokes literally burned into boards with an acetylene torch — the transmutation of art into gold, and the human body recorded as a burn mark.

Calligraffiti embodies heat in a different sense — calligraphy as subversive act, the gesture as embodiment of revolutionary fire and fervour, the art of incendiarism, of inflammatory writing. Burroughs identified Gysin's calligraphy with the "silent writing" of Hassan i Sabbah — that is, writing which may be 'read' but cannot be decoded or spoken, a vehicle for the transmission of an esoteric knowledge for initiates and adepts. The connection with Sabbah is crucial because Gysin's calligraphy, existing between painting and writing, is interpreted by Burroughs as a secret weapon, an incendiary instrument which carries a radical, heretical message, and this would actually become part of the work's intent. Like the mysterious transmissions sent out from Alamout to the Assassins, a renegade "telegraph" system inspiring acts of subversion and revolt, Gysin's "silent writing" would be understood as the magical communication of political subversion, inspiring the overthrow of the orthodox and the status quo. It may be read as a form of invective, like the language which blazes forth from Gysin's Uher and the written page, a splenetic outpouring, lacerating, vituperative, an unleashing of rhetoric — language impelled by the desire to attack, a version of the scurrilous Roman psogoi. Gysin and Burroughs' use of the Sabbah model was both metaphoric and literal but what is certain is that the notion of polemical power became an inextricable component of Gysin's visual art, and in Calligraffiti the Old Master sends out his final heresy, his terminal call-to-arms: "Towers Open Fire!" The picture, full of attack and abandon in its fiery gestures, its forms coiling and unleashed, incarnates the spirit of the Hash Heads of Alamout as they sally forth on a suicidal murder mission.

Ian MacFadyen and Dreamachine, 2008 (Photograph by Jonathan Greet)

Nik Sheehan's [excellent documentary film FLicKeR]6 has been shown as part of the October Gallery's Gysin exhibition and visitors also have the opportunity to view two new versions of the Dreamachine. It's clear that Gysin's flaming calligraphy is symbiotically connected to the unfolding patterns created by flicker, a phenomenon which may be experienced as flames shooting out of the rotating cylinder, while the form of Calligraffiti, with its calligraphy running on continuously from panel to panel, is itself suggestive of the continuum of the Dreamachine. In Sheehan's film Kenneth Anger speculates that hallucinatiory vision and the creation of art both originated in the contemplation of fire and in the receptive dreaming state produced by the inexhaustible flicker of flames in which no flame repeats itself — the plenitude of fire, as described by Gaston Bachelard in [The Psychoanalysis of Fire]7 . Certainly, to view Calligraffiti after using a dreamachine is to gain insight into the genetic links between Gysin's art forms and in particular the absolute primacy of rhythm throughout his work. In calligraphy, prose, poetry, song and the Dreamachine, it is the experience of variety and permutation through a continual run-on and runaway measure which is so striking, an endless turning and unfolding, repetition and superimposition, the creation of a self-engendering, self-perpetuating experience of flux which is implicit in the form of the work and mirrored in the firing neural patterns of the brain. The cut-up too is part of this matrix in which art works appear to become autonomous and escape fixity — and the razor's cuts, too, create a rhythm, a mechanical staccato like a train running over tracks or a film reel rattling around and around on a spool. Gysin's greatest achievement was not in the disembodied creation of machine art, but in the setting free of the work, the pleasure and fascination inherent in seeing and feeling patterns and words and images take on lives of their own. His procedures both make the observer and reader conscious of the acts of looking and reading, and allow them to become immersed and lost in the experience, caught up and mesmerized. Such is the process — the sundering of boundaries and categories, the privileging of the play and metamorphosis of form, and the intuition of limitlessness wonder beyond grasp and meaning.

". . . the sprout is the spring of green life . . . From the centre of ME within the grain, I shoot up one bursting letter written in that air which is nothing till I write it." Gysin's calligraphy derives from the cursive grass script, and he pursued this botanical and aesthetic analogy as he searched for his own, unique, talismanic, calligraphic signature, finding it in the bean sprout, the soya "whose explosive power can overturn monuments." He understood the calligraphic gestures which emerged from this seed pod, an emblematic device transforming his written name into an image of contained explosive power, as the shooting and burgeoning tendrils of an uncontainable life force linked to the hallucinatory properties of plants. Describing the datura plant, he wrote: ". . . that flower had just bloomed and was still full of its rocketing strength. When I plucked it, it emitted a cry! . . . I appreciate plants quite differently since then. Immediately all around me I saw the entire garden alive. Everything, everything, all the flowers and plants and even each blade of grass was turning toward the setting sun by small sudden clicks. Everything was alive like me on this earth, everything was breathing." His discovery and adoption of the seed pod motif which bursts and rockets with flowering arabesques of life, crystallized the equation between plant life and sound: the smoking of kif would evoke the music of JouJouka, cannabis synaesthetically conjuring the rhyhms of the riata, gimbri and lyre, while the the smoking of hashish suggested visions of the lush Paradise Garden of Hassan i Sabbah. The calligraphic script, the rites of Pan, hallucination, riot and music are all connected through the myth of Pan who made a pipe from a split weed in order to woo Syrinx. The calligraphic sign, the music, the dope — all derive from the plant world and so lead Gysin to make correspondences between myth and the natural world, art and botany, sound and visual hallucination, and to systematically explore their synaesthetic relations. The musical analogy is fraught with contradiction — as ever with Gysin: he believed music was a war machine and the music of joujouka was at some level for him not only a healing music, an invitation to trance, but a call to arms, the inspiration of usurpation, the very rhythm of revolt.

The calligraphic gesture is a cut through space and time, and Gysin would recall witnessing the last public execution by guillotine in Paris, the definitive act of slicing through life. The 'Way of the Brush' was also for Gysin a form of shamanic dismemberment — the magical passes of the brush cut through space, leaving slashes and wounds and deep cuts through which the ink or paint bleeds into the surface of the reliquary paper or canvas, and the very gestures made by arm and wrist and fingers are 'immortalized' by these fatal, fateful lesions. Tony Balch's film Cut-Ups shows Gysin literally attacking the picture surface as well as coaxing and caressing it — it is an erotic physical act, as violent as it is tender, as percussive as it is a series of brief or lingering strokes. The brush hits and strikes and is then dragged and twisted or lifted in a long carress, tapering away or cast off before resuming a different course, a variation, a permutation — always unique, but part of an eternal sequence of possible strokes and flicks, dashes and flourishes. Rhythm is all — and Gysin's calligraphy inviting a 'reading' beyond literal decipherment, is linked to his incantatory but broken, improvisatory yet metred song raps and word plays. It is the visceral rush of inspiration, the physical body in action, and the play of variation which Gysin relished in all its forms — visual, lexical, aural, and their libidinal congress and synaesthetic communion.

All those great stories about bad luck and hexes, personal disasters and losses — Gysin broadcast these as a litany of lamentation. Fleeced of his restaurant 1001 Nights, out with just the shirt on his back — that was his story. Kicked out of the Surrealist movement, his article on Alamout rejected by Rolling Stone Magazine, the failure of the Dreamachine to sell a million . . . Burroughs' "Project For Disastrous Success" perfectly captures Gysin's martyrdom and woe, athough this was done almost always with great style and gusto, an enjoyable immolation, yes, and of course there was always some truth to it, a real case to be answered. Perhaps the truly splenetic is always at some level self-lacerating, and Gysin was a master of both self-abnegation and the terminal put-down. Rubbing out the word was a way of rubbing out the self, erasing his own name and sign, and necessarily a masochistic act of self-subversion at some level, a confusion about his own identity and very being. If, as Terry Wilson has said, "Contradiction was their Method," then in Gysin's case this included the undermining of his own reputation. Burroughs told me, "There was a step which Brion would not take . . . " Perhaps the default mechanism was a kind of perverse self-preservation, never to relinquish the special domain of outsiderhood, invention and playfulness. Reputation and status weigh heavy on the shoulders of born mischief-makers and though Gysin's reputation is assured, it's always, as ever, only just so far, and then never, ever enough. He will remain a painter's painter, as we used to say, way back when, before the art was on the money, and the serious money was on the less-than-serious art. He is fated, as he certainly knew, to appeal to a certain esoteric constituency, forever branded the man who did too many things, and did them all too well. His attacks on the vulgar market place were too true not to rebound upon him with a vengeance, and if his refusal to be co-opted went hand-in-hand with the desire for fame and fortune, in the end he was reconciled to having done what he could — and a lot more besides! In this sense, Calligraffiti is the double consummation of Gysin's name — a consummate act, and one consumed by fire, the name rubbed out, and the name immortalized. The name will be remembered because he did indeed erase it — the double act of a true master of paradox.

Francesco Rimondi, Terry Wilson and Ian MacFadyen with Dreamachine, 2008 (Photograph by Jonathan Greet)

With a big brush Gysin stabbed the canvas, pulled and twisted his magic wand in space, catching desire by the tail, shooting forth the phallic sign of sexuality for its own sake, an erotic Pandemic beyond procreation, the pleasure principle above the biological imperative. But this painting is as elegiac as it is festive, a paradoxical work of profound mourning which is carnivalesque in its exuberance and brightness. These inspired, dancing, bold calligraphic strokes are literally the final traces, the Last Words and Testament, the Dance of Fire performed as a death rite, a real Bonfire of the Vanities, taking us from primordial chaos to a great and terminal immolation . . . Everything in the artist's creative life is subliminally referenced in this painting which travels horizontally through the Bardo and consigns the body and the body of work alike to the fire. "A death trip?", Gysin liked to ask, "what other kind of trip are we on?" Calligraffiti of Fire was the last dream of a dying mythomaniac, the seduction of Pan and the destruction of Kali become one, and cancer at the door with a singing telegram. This should be heard as a Blues rendition of Really Bad News — Gysin's favourite music was the duende of black culture, jubilant and broken-hearted, hot and sexy, soulful and full of suffering and protest, playful, direct, moving and extraordinarily sophisticated. He incarnated the same qualities of celebration and despair and artfulness in his own songs and art and writing, he recognized himself in that culture of otherness which he also heard in the swirls and blasts of the Moroccan riata. It really was Everything or Nothing for Gysin — to become other, and to disown one's self, whoever or whatever that might be, to confound race and sex and genes and nationality, that was the impossible death-in-life process which he pursued through work which reverses the accepted idea of art as self-realization — his aim was the erasure of personal identity, to disappear entirely into the creation, the illusion, especially when playing and punning on his own given Christian name and the name of the Father. However often he proselytized the heretical in all its variations, or employed it as creed or manifesto, it is as if Gysin could not access the true meaning or purpose of his perverse desire to unmake and undo himself — as if the process of deconstruction was a pure form of transcendence and free from any psychopathological motivation, a detached experiment devoid of causal contamination. It is significant that Gysin diagnosed Burroughs as suffering from possession by an Ugly Spirit, the malign entity of a traumatized past, but was unwilling or unable to discover any such comparable daemon in his own psyche. But his desire to become another was more than a homage to Rimbaud and his own declared program of spiritual demolition is suggestive of nothing less than a fated, pre-emptive strategy for outwitting death, an abnegation which rebounded in his long drawn-out, pain-filled demise. As ever, the final acceptance of mortality always leaves a space for denial, a remaining, absolute, biological incomprehension. If not to survive, then to leave a trace of having existed. And at some level, that is what the grand gesture of Calligraffiti is all about. By his mark shall you know him, and thereby remember him. Graffiti on a wall: Brion Gysin Was Here.

At the same time, naturally: total annihilation of the individual, a terminal disappearing act. "I mean to get out of here and come back again never!" Radical dispersal: gestures as magical passes caught at the critical moment between implosion and explosion. Oblivion, as big as he could paint it, as he stared right into it. A testament of despair, written in letters of fire. "A story like this can have no happy ending. Or can it?" Gysin loved Dante's Inferno and if he found his own transcendent Sahara transformed by Dante into a Hell, then he recognized that it had always been that way — ring doves and snakes, beauty and terror, life and art created and consumed in the same inner spiritual flame. Calligraffiti of Fire is the celebration of an Auto Da Fe, a long last sweeping look at the blazing summer panorama, fields rippling with light and life, that moment of awareness and arousal and acceptance when everything is just waiting to begin, the spinning, ecstatic, disoriented view from a darkened but sun-dazzled doorway of the plenitude and possibility and mystery of life opening out like a makemono, blinding white page upon page — and then the sun goes out and eyes close forever. It was all a kif dream, after all, wasn't it? Yes, a beautiful illusion, a Paradise Garden now reduced to the stone ruins of a renegade fortress. Archers, prepare your arrows of fire! The Golden Elixir is acrylic paint on a picture which could be worth a truly considerable sum one of these days, though then again, don't bank on it — as Brion Gysin knew only too well, and as we're finding out right now, money is the greatest illusion of all, the one we are helplessly invested in. Gysin painted and wrote illusion, because that was both the key and lock of his philosophy : All is Maya, and long may Maya reign, and here's Brion Gysin's version of the whirl . . . He had written and painted as he had lived — flamboyant and careful, classical and revolutionary, narcissistic and self-loathing. Calligraffiti is the contradictory bittersweet farewell of a misanthropist who loved life, an artist who recognized beauty and suffered the anguish of the abyss, doomed to live and love, and blessed to die. It is a paean and a conflagration, a hymn to the fire of inspiration sung with ashes on the lips:

And slowly, slowly dropping over all

The sand, there drifted down huge flakes of fire . . .

Even so rained down the everlasting heat,

And, as steel kindles tinder, kindled the sands,

Redoubling pain . . .

Brion Gysin: Calligraffiti of Fire

11 December 2008 — 7 February 2009

October Gallery

24 Old Gloucester Street

London WC1N 3AL

To the Memory of Karen Trusselle, a beautiful artist. Text written by Ian MacFadyen, London, December 2008. Published by RealityStudio on 14 January 2009. Ian MacFadyen offers his special thanks to Kathelin Gray and everyone at the October Gallery; to Terry Wilson; and to Jonathan Greet.